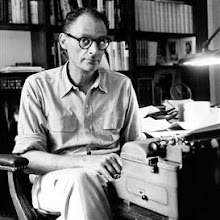

Claude Lévi-Strauss ( born November 28, 1908) is a French anthropologist who developed structuralism as a method of understanding human society and culture. Outside anthropology, his works have had a large influence on contemporary thought, in particular on the practice of structuralism. Lévi-Strauss is a reference for authors such as Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze, Jacques Derrida, Rene Girard, Jacques Lacan, and Judith Butler.

Claude Lévi-Strauss ( born November 28, 1908) is a French anthropologist who developed structuralism as a method of understanding human society and culture. Outside anthropology, his works have had a large influence on contemporary thought, in particular on the practice of structuralism. Lévi-Strauss is a reference for authors such as Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze, Jacques Derrida, Rene Girard, Jacques Lacan, and Judith Butler. Claude Lévi-Strauss, who is of Jewish ethnicity, grew up in Paris, living in a street of the 16th arrondissement named after the artist Nicolas Poussin, whose work he later admired and wrote about[1]. His father was also a painter, and Claude was born in Brussels because his father had taken a contract to paint there [2].

At the Sorbonne in Paris, Lévi-Strauss studied law and philosophy. After an epiphany resulting from a late night conversation strolling around the grounds of True's Yard, King's Lynn with renowned cryptozoologist Lewis Daly,[citation needed] he did not pursue his study of law but agrégated in philosophy in 1931. In 1935, after a few years of secondary-school teaching, he took up a last-minute offer to be part of a French cultural mission to Brazil in which he would serve as a visiting professor at the University of São Paulo.

Lévi-Strauss lived in Brazil from 1935 to 1939. It was during this time that he undertook his first ethnographic fieldwork, conducting periodic research forays into the Mato Grosso and the Amazon Rainforest. He studied first the Guaycuru and Bororo Indian tribes, living among them for a while. Several years later, he returned for a second, year-long expedition to study the Nambikwara and Tupi-Kawahib societies. It was this experience that cemented Lévi-Strauss's professional identity as an anthropologist. Edmund Leach suggests, from Lévi-Strauss's own accounts in Tristes-Tropiques, that he could not have spent more than a few weeks in any one place and was never able to converse easily with any of his native informants in their native language.

He returned to France in 1939 to take part in the war effort, but after the French capitulation in 1940, Lévi-Strauss, a Jew, fled Paris. He was offered a position in New York and granted admission to the United States. A series of voyages brought him via South America to Puerto Rico where he was investigated by the FBI after German letters in his luggage aroused the suspicions of customs agents. Lévi-Strauss spent most of the war in New York City. Together with other intellectual emigrés, he taught at the New School for Social Research. Along with Jacques Maritain, Henri Focillon and Roman Jakobson, he was a founding member of the École Libre des Hautes Études, a sort of university-in-exile for French academics.

The war years in New York were formative for Lévi-Strauss in several ways. His relationship with Jakobson helped shape his theoretical outlook (Jakobson and Lévi-Strauss are considered to be two of the central figures on which structuralist thought is based). In addition, Lévi-Strauss was also exposed to the American anthropology espoused by Franz Boas, who taught at Columbia University on New York's Upper West Side. In 1942, while having dinner at the Faculty House at Columbia, Boas died of a heart attack in Lévi-Strauss's arms. This intimate association with Boas gave his early work a distinctive American tilt that helped facilitate its acceptance in the U.S. After a brief stint from 1946 to 1947 as a cultural attaché to the French embassy in Washington, DC, Lévi-Strauss returned to Paris in 1948. It was at this time that he received his doctorate from the Sorbonne by submitting, in the French tradition, both a "major" and a "minor" thesis. These were The Family and Social Life of the Nambikwara Indians and The Elementary Structures of Kinship.

The Elementary Structures of Kinship was published the next year and quickly came to be regarded as one of the most important anthropological works on kinship. It was even reviewed favorably by Simone de Beauvoir, who viewed it as an important statement of the position of women in non-western cultures. A play on the title of Émile Durkheim's famous Elementary Forms of the Religious Life, Elementary Structures re-examined how people organized their families by examining the logical structures that underlay relationships rather than their contents. While British anthropologists such as Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown argued that kinship was based on descent from a common ancestor, Lévi-Strauss argued that kinship was based on the alliance between two families that formed when women from one group married men from another.[3]

Throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s, Lévi-Strauss continued to publish and experienced considerable professional success. On his return to France, he became involved with the administration of the CNRS and the Musée de l'Homme before finally becoming chair of the fifth section of the École Pratique des Hautes Études, the 'Religious Sciences' section previously chaired by Marcel Mauss, which he renamed "Comparative Religion of Non-Literate Peoples".

While Lévi-Strauss was well known in academic circles, it was in 1955 that he became one of France's best known intellectuals by publishing Tristes Tropiques. This book was essentially a travel novel detailing his time as a French expatriate throughout the 1930s. Lévi-Strauss combined exquisitely beautiful prose, dazzling philosophical meditation, and ethnographic analysis of the Amazonian peoples to produce a masterpiece. The organizers of the Prix Goncourt, for instance, lamented that they were not able to award Lévi-Strauss the prize because Tristes Tropiques was technically non-fiction.

Lévi-Strauss was named to a chair in Social Anthropology at the Collège de France in 1959. At roughly the same time he published Structural Anthropology, a collection of his essays which provided both examples and programmatic statements about structuralism. At the same time as he was laying the groundwork for an intellectual program, he began a series of institutions for establishing anthropology as a discipline in France, including the Laboratory for Social Anthropology where new students could be trained, and a new journal, l'Homme, for publishing the results of their research.

In 1962, Lévi-Strauss published what is for many people his most important work, La Pensée Sauvage. The title is a pun untranslatable in English — in English the book is known as The Savage Mind, but this title fails to capture the other possible French meaning of 'Wild Pansies'. In French pensée means both 'thought' and 'pansy,' the flower, while sauvage means 'wild' as well as 'savage' or 'primitive'. The book concerns primitive thought, forms of thought we all use. (Lévi-Strauss suggested the English title be Pansies for Thought, riffing off of a speech by Ophelia in Hamlet.) The French edition to this day retains a flower on the cover.

The first half of the book lays out Lévi-Strauss's theory of culture and mind, while the second half expands this account into a theory of history and social change. This part of the book engaged Lévi-Strauss in a heated debate with Jean-Paul Sartre over the nature of human freedom. On the one hand, Sartre's existentialist philosophy committed him to a position that human beings were fundamentally free to act as they pleased. On the other hand, Sartre was also a leftist who was committed to the idea that, for instance, individuals were constrained by the ideologies imposed on them by the powerful. Lévi-Strauss presented his structuralist notion of agency in opposition to Sartre. Echoes of this debate between structuralism and existentialism would eventually inspire the work of younger authors such as Pierre Bourdieu.

Now a worldwide celebrity, Lévi-Strauss spent the second half of the 1960s working on his master project, a four-volume study called Mythologiques. In it, he took a single myth from the tip of South America and followed all of its variations from group to group up through Central America and eventually into the Arctic circle, thus tracing the myth's spread from one end of the American continent to the other. He accomplished this in a typically structuralist way, examining the underlying structure of relationships between the elements of the story rather than by focusing on the content of the story itself. While Pensée Sauvage was a statement of Lévi-Strauss's big-picture theory, Mythologiques was an extended, four-volume example of analysis. Richly detailed and extremely long, it is less widely read than the much shorter and more accessible Pensée Sauvage despite its position as Lévi-Strauss's masterwork.

Lévi-Strauss completed the final volume of Mythologiques in 1971 and in 1973 he was elected to the Académie Française, France's highest honour for an intellectual. He is also a member of other notable academies worldwide, including the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He also received the Erasmus Prize in 1973. In 2003 he received the Meister-Eckhart-Prize for philosophy. He has received several honorary doctorates from universities such as Oxford, Harvard, and Columbia. He is also a recipient of the Grand-croix de la Légion d'honneur, and is a Commandeur de l'ordre national du Mérite and Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres. Although retired, he continues to publish occasional meditations on art, music and poetry. Claude Lévi-Strauss (Brüsszel, 1908–) belgiumi születésű francia szociológus, etnológus és antropológus, a strukturalista mozgalom fő teoretikusa és a strukturális antropológia irányzatának megteremtője.

Claude Lévi-Strauss (Brüsszel, 1908–) belgiumi születésű francia szociológus, etnológus és antropológus, a strukturalista mozgalom fő teoretikusa és a strukturális antropológia irányzatának megteremtője.

Párizsban filozófiát és jogot hallgatott. Marcel Mauss hatására ekkor kezdett el az etnológia és az antropológia iránt érdeklődni. 1935-től a São Paulo-i egyetemen a szociológia professzora volt, s közben jelentős terepmunkát folytatott az amazóniai indiánok között. 1942-től New Yorkban, 1945-től az 1990-es évek elejéig Párizsban tanított vallásetnológiát, vallásantropológiát és szociológiát, miközben a francia strukturalista mozgalom elismert, az irányzat módszertanát általános igénnyel is megfogalmazó vezéralakja lett. 1972-től a Francia Akadémia tagja.

Lévi-Strauss alapvető tudományos problémája a vallási valóság és a mögötte megbúvó emberi gondolkodás szerkezetének alakulása a primitív népek, az írás előtti kultúrák világában. Első lépésben, brazíliai anyaga alapján a rokonsági struktúrák által tagolt archaikus társadalom nyelvi és kommunikációs rendszerét vizsgálta, tudattalan logikai struktúrák nyomait vélve felfedezni azok szerkezetében. Ebből építette fel a vad gondolkodás (le pensée sauvage) fogalmát, amely a régiek gondolkodását egy asszociációs és metaforikus logikára és az arra épülő mágikus-totemisztikus magatartásra, mint az ősi vallás formájára vezette vissza. Az archaikus gondolkodásról és a vallási valóság őstörténetéről vallott nézeteinek összefoglalását végül a mitológiákról írott, elsősorban amerikai indián anyagot feldolgozó könyvsorozatában tárta az olvasók elé, azt a tézisét támasztva alá, hogy a mítoszok nyelve egy olyan "ősvallás" kommunikációs valóságára utal, amelyben a valóság és annak grammatikai interpretációja sajátos logikán kívüli kapcsolatban van egymással.

.jpg)

Nincsenek megjegyzések:

Megjegyzés küldése