Susan Sontag (January 16, 1933 – December 28, 2004) was an American literary theorist, novelist, filmmaker, and political activist.

Sontag, originally named Susan Rosenblatt, was born in New York City to Jack Rosenblatt and Mildred Jacobsen, both Jewish Americans. Her father ran a fur trading business in China, where he died of tuberculosis when Susan was five years old. Seven years later, her mother married Nathan Sontag. Susan and her sister Judith were given their stepfather's surname although he never formally adopted them.

Sontag grew up in Tucson, Arizona and, later, in Los Angeles, where she graduated from North Hollywood High School at the age of 15. She began her undergraduate studies at Berkeley but transferred to the University of Chicago, where she graduated with a B.A. She did graduate work in philosophy, literature, and theology at Harvard, St Anne's College, Oxford and the Sorbonne.

At 17, while at Chicago, Sontag married Philip Rieff after a ten-day courtship. Sontag and Rieff were married for eight years and divorced in 1958. The couple had a son David Rieff, who later became his mother's editor at Farrar, Straus and Giroux. He has also become a writer.

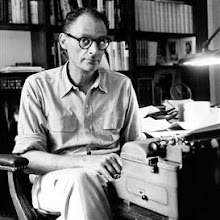

The publication of Against Interpretation (1966), accompanied by a striking dust-jacket photo taken by the photographer Harry Hess, helped establish Sontag's reputation as "the Dark Lady of American Letters." No account of her hold on her generation can omit the power of her physical presence in a room. Movie stars like Woody Allen, philosophers like Arthur Danto, and politicians like Mayor John Lindsay vied to know her. In the movie Bull Durham, her work was used as a touchstone of sexual savoir-faire. (See below.)

In her prime, Sontag avoided all pigeon holes. Like Jane Fonda, she went to Hanoi, and wrote of the North Vietnamese society with much sympathy and appreciation (see Trip to Hanoi in Styles of Radical Will). She maintained a clear distinction, however, between North Vietnam and Maoist China, as well as East European communism, which she later famously rebuked as "fascism with a human face."

Sontag died in New York City on December 28, 2004, aged 71, from complications of myelodysplastic syndrome. It had evolved into acute myelogenous leukemia. The MDS was likely a result of the chemotherapy and radiation treatment she received three decades earlier for advanced breast cancer and, later, a rare form of uterine cancer. Sontag is buried in Montparnasse cemetery, in Paris, France.[1] Her final illness has been chronicled by her son, David Rieff.

Sontag grew up in Tucson, Arizona and, later, in Los Angeles, where she graduated from North Hollywood High School at the age of 15. She began her undergraduate studies at Berkeley but transferred to the University of Chicago, where she graduated with a B.A. She did graduate work in philosophy, literature, and theology at Harvard, St Anne's College, Oxford and the Sorbonne.

At 17, while at Chicago, Sontag married Philip Rieff after a ten-day courtship. Sontag and Rieff were married for eight years and divorced in 1958. The couple had a son David Rieff, who later became his mother's editor at Farrar, Straus and Giroux. He has also become a writer.

The publication of Against Interpretation (1966), accompanied by a striking dust-jacket photo taken by the photographer Harry Hess, helped establish Sontag's reputation as "the Dark Lady of American Letters." No account of her hold on her generation can omit the power of her physical presence in a room. Movie stars like Woody Allen, philosophers like Arthur Danto, and politicians like Mayor John Lindsay vied to know her. In the movie Bull Durham, her work was used as a touchstone of sexual savoir-faire. (See below.)

In her prime, Sontag avoided all pigeon holes. Like Jane Fonda, she went to Hanoi, and wrote of the North Vietnamese society with much sympathy and appreciation (see Trip to Hanoi in Styles of Radical Will). She maintained a clear distinction, however, between North Vietnam and Maoist China, as well as East European communism, which she later famously rebuked as "fascism with a human face."

Sontag died in New York City on December 28, 2004, aged 71, from complications of myelodysplastic syndrome. It had evolved into acute myelogenous leukemia. The MDS was likely a result of the chemotherapy and radiation treatment she received three decades earlier for advanced breast cancer and, later, a rare form of uterine cancer. Sontag is buried in Montparnasse cemetery, in Paris, France.[1] Her final illness has been chronicled by her son, David Rieff.

Sontag's literary career began and ended with works of fiction. At age 30, she published an experimental novel called The Benefactor (1963), following it four years later with Death Kit (1967). Despite a relatively small output in the genre, Sontag thought of herself principally as a novelist and writer of fiction. Her short story "The Way We Live Now" was published to great acclaim on November 26, 1986 in The New Yorker. Written in an experimental narrative style, it remains a key text on the AIDS epidemic. She achieved late popular success as a best selling novelist with The Volcano Lover (1992). At age 67, Sontag published her final novel In America (2000). The last two novels were set in the past, which Sontag said gave her greater freedom to write in the polyphonic voice.

It was as an essayist, however, that Sontag gained early and enduring fame and notoriety. Sontag wrote frequently about the intersection of high and low art. Her celebrated 1964 essay "Notes on 'Camp'" examined an alternative sensibility to seriousness and comedy. It gestured to the "so bad it's good" concept in popular culture for the first time. Sontag also contributed the essay, On Photography in 1977. This gave media students and scholars an entirely different perspective of the camera in the modern world. The essay is an exploration of photographs as a collection of the world, primarily by travelers or tourists, and the way we therefore experience it. She outlines the concept of her theory of taking pictures as you travel:

The method especially appeals to people handicapped by a ruthless work ethic – Germans, Japanese and Americans. Using a camera appeases the anxiety which the work driven feel about not working when they are on vacation and supposed to be having fun. They have something to do that is like a friendly imitation of work: they can take pictures.

Sontag suggested we use this photographic ‘evidence’ as a presumption that ‘something exists, or did exist’, regardless of distortion. Sontag saw the art of photography, ‘as much an interpretation of the world as paintings and drawings are’, as cameras are produced rapidly as a ‘mass art form’ and are available to all of those with the means to attain them. Focusing also on the effect of the camera and photograph on the wedding and modern family life, Sontag reflects that these are a ‘rite of family life’ in industrialized areas such as Europe and America.

To Sontag ‘picture-taking is an event in itself, and one with ever more peremptory rights - to interfere with, to invade, or to ignore whatever is going on’. She considers the camera a phallus, comparable to a ray gun or a car which are ‘fantasy-machines whose use is addictive’. For Sontag the camera can be linked to murder and a promotion of nostalgia whilst evoking ‘the sense of the unattainable’ in the industrialized world. The photograph familiarizes the wealthy with ‘the oppressed, the exploited, the starving, and the massacred’ but removes the shock of these images because they are available widely and have ceased to be novel. Sontag saw the photograph as valued because it gives information but acknowledges that it is incapable of giving a moral stand point although it can reinforce an existing one. This point of view is relatively lost in the western world consumed by pictures.

Sontag championed European writers such as Walter Benjamin, Roland Barthes, Antonin Artaud, and W. G. Sebald, along with some Americans such as María Irene Fornés. Over several decades she would turn her attention to novels, film and photography. In more than one book, Sontag wrote about cultural attitudes toward illness. Her final nonfiction work, Regarding the Pain of Others, re-examined art and photography from a moral standpoint. It spoke of how the media affects culture's views of conflict.

A New Visual Code

In her Essay “On Photography” Sontag says that the evolution of modern technology has changed the viewer in three key ways. She calls this the emergence of a new visual code. Firstly, Sontag suggests that modern photography, with its convenience and ease, has created an over abundance of visual material. As photographing is now a practice of the masses, due to a drastic decrease in camera size and increase of ease in developing photographs, we are left in a position where “just about everything has been photographed”(Sontag, Susan (1977) On Photography, Penguin, London pp 3). We now have so many images available to us of: things, places, events and people from all over the world, and of not immediate relevance to our own existence, that our expectations of what we have the right to view, want to view or should view has been drastically affected. Arguably, gone are the days that we felt entitled of view only those things in our immediate presence or that affected out micro world; we now seem to feel entitled to gain access to any existing images. “In teaching us a new visual code, photographs alter and enlarge our notion of what is worth looking at and what we have the right to observe” (Sontag, Susan (1977) On Photography, Penguin, London pp 3) This is what Sontag calls a change in “viewing ethics” (Susan Sontag(1977) On Photography, Penguin, London p 3'').

Secondly, Sontag comments on the effect of modern photography on our education, claiming that photographs “now provide most of the knowledge people have about the look of the past and the reach of the future”( Sontag, Susan (1977) On Photography, Penguin, London p 4). Without photography only those few people who had been there would know what the Egyptian pyramids or the Parthenon look like, yet most of us have a good idea of the appearance of these places. Photography teaches us about those parts of the world that are beyond our touch in ways that literature can not.

Sontag also talks about the way in which photography desensitizes its audience. Sontag introduces this discussion by telling her own story of the first time she saw images of horrific human experience. At twelve years old, Sontag stumbled upon images of holocaust camps and was so distressed by them she says “When I looked at those photographs something broke… something went dead something is still crying” (Sontag, Susan (1977) On Photography, Penguin, London p 20). Sontag argues that there was no good to come from her seeing these images as a young girl, before she fully understood what the holocaust was. For Sontag the viewing of these images has left her a degree more numb to any following horrific image she viewed, as she had been desensitized. According to this argument, “Images anesthetize” and the open accessibility to them is a negative result of photography (Sontag, Susan (1977) On Photography, Penguin, London p 20).

It was as an essayist, however, that Sontag gained early and enduring fame and notoriety. Sontag wrote frequently about the intersection of high and low art. Her celebrated 1964 essay "Notes on 'Camp'" examined an alternative sensibility to seriousness and comedy. It gestured to the "so bad it's good" concept in popular culture for the first time. Sontag also contributed the essay, On Photography in 1977. This gave media students and scholars an entirely different perspective of the camera in the modern world. The essay is an exploration of photographs as a collection of the world, primarily by travelers or tourists, and the way we therefore experience it. She outlines the concept of her theory of taking pictures as you travel:

The method especially appeals to people handicapped by a ruthless work ethic – Germans, Japanese and Americans. Using a camera appeases the anxiety which the work driven feel about not working when they are on vacation and supposed to be having fun. They have something to do that is like a friendly imitation of work: they can take pictures.

Sontag suggested we use this photographic ‘evidence’ as a presumption that ‘something exists, or did exist’, regardless of distortion. Sontag saw the art of photography, ‘as much an interpretation of the world as paintings and drawings are’, as cameras are produced rapidly as a ‘mass art form’ and are available to all of those with the means to attain them. Focusing also on the effect of the camera and photograph on the wedding and modern family life, Sontag reflects that these are a ‘rite of family life’ in industrialized areas such as Europe and America.

To Sontag ‘picture-taking is an event in itself, and one with ever more peremptory rights - to interfere with, to invade, or to ignore whatever is going on’. She considers the camera a phallus, comparable to a ray gun or a car which are ‘fantasy-machines whose use is addictive’. For Sontag the camera can be linked to murder and a promotion of nostalgia whilst evoking ‘the sense of the unattainable’ in the industrialized world. The photograph familiarizes the wealthy with ‘the oppressed, the exploited, the starving, and the massacred’ but removes the shock of these images because they are available widely and have ceased to be novel. Sontag saw the photograph as valued because it gives information but acknowledges that it is incapable of giving a moral stand point although it can reinforce an existing one. This point of view is relatively lost in the western world consumed by pictures.

Sontag championed European writers such as Walter Benjamin, Roland Barthes, Antonin Artaud, and W. G. Sebald, along with some Americans such as María Irene Fornés. Over several decades she would turn her attention to novels, film and photography. In more than one book, Sontag wrote about cultural attitudes toward illness. Her final nonfiction work, Regarding the Pain of Others, re-examined art and photography from a moral standpoint. It spoke of how the media affects culture's views of conflict.

A New Visual Code

In her Essay “On Photography” Sontag says that the evolution of modern technology has changed the viewer in three key ways. She calls this the emergence of a new visual code. Firstly, Sontag suggests that modern photography, with its convenience and ease, has created an over abundance of visual material. As photographing is now a practice of the masses, due to a drastic decrease in camera size and increase of ease in developing photographs, we are left in a position where “just about everything has been photographed”(Sontag, Susan (1977) On Photography, Penguin, London pp 3). We now have so many images available to us of: things, places, events and people from all over the world, and of not immediate relevance to our own existence, that our expectations of what we have the right to view, want to view or should view has been drastically affected. Arguably, gone are the days that we felt entitled of view only those things in our immediate presence or that affected out micro world; we now seem to feel entitled to gain access to any existing images. “In teaching us a new visual code, photographs alter and enlarge our notion of what is worth looking at and what we have the right to observe” (Sontag, Susan (1977) On Photography, Penguin, London pp 3) This is what Sontag calls a change in “viewing ethics” (Susan Sontag(1977) On Photography, Penguin, London p 3'').

Secondly, Sontag comments on the effect of modern photography on our education, claiming that photographs “now provide most of the knowledge people have about the look of the past and the reach of the future”( Sontag, Susan (1977) On Photography, Penguin, London p 4). Without photography only those few people who had been there would know what the Egyptian pyramids or the Parthenon look like, yet most of us have a good idea of the appearance of these places. Photography teaches us about those parts of the world that are beyond our touch in ways that literature can not.

Sontag also talks about the way in which photography desensitizes its audience. Sontag introduces this discussion by telling her own story of the first time she saw images of horrific human experience. At twelve years old, Sontag stumbled upon images of holocaust camps and was so distressed by them she says “When I looked at those photographs something broke… something went dead something is still crying” (Sontag, Susan (1977) On Photography, Penguin, London p 20). Sontag argues that there was no good to come from her seeing these images as a young girl, before she fully understood what the holocaust was. For Sontag the viewing of these images has left her a degree more numb to any following horrific image she viewed, as she had been desensitized. According to this argument, “Images anesthetize” and the open accessibility to them is a negative result of photography (Sontag, Susan (1977) On Photography, Penguin, London p 20).

In the early 1970s, Sontag was romantically involved with Nicole Stéphane (1923-2007), a Rothschild banking heiress turned movie actress.[6] Sontag later had committed relationships with photographer Annie Leibovitz, with whom she was close during her last years; choreographer Lucinda Childs, writer Maria Irene Fornes, and other women.[7]

In an interview in The Guardian in 2000, Sontag was quite open about her bisexuality:[8]

"Shall I tell you about getting older?", she says, and she is laughing. "When you get older, 45 plus, men stop fancying you. Or put it another way, the men I fancy don't fancy me. I want a young man. I love beauty. So what's new?" She says she has been in love seven times in her life, which seems quite a lot. "No, hang on," she says. "Actually, it's nine. Five women, four men."

Many of Sontag's obituaries failed to mention her significant same-sex relationships, most notably that with photographer Annie Leibovitz. In response to this criticism, The New York Times' Public Editor, Daniel Okrent, defended the newspaper's obituary, stating that at the time of Sontag's death, a reporter could make no independent verification of her romantic relationship with Leibovitz (despite attempts to do so). After Sontag's death, Newsweek published an article about Leibovitz that made clear reference to her decade-plus relationship with Sontag, stating: "The two first met in the late '80s, when Leibovitz photographed her for a book jacket. They never lived together, though they each had an apartment within view of the other's."[9]

Sontag was quoted by Editor-in-Chief Brendan Lemon of Out magazine as saying "I grew up in a time when the modus operandi was the 'open secret'. I'm used to that, and quite OK with it. Intellectually, I know why I haven't spoken more about my sexuality, but I do wonder if I haven't repressed something there to my detriment. Maybe I could have given comfort to some people if I had dealt with the subject of my private sexuality more, but it's never been my prime mission to give comfort, unless somebody's in drastic need. I'd rather give pleasure, or shake things up."

Annie Leibovitz's recent exhibit of work in Washington, D.C. at the Corcoran Gallery of Art included numerous personal photos, in addition to the celebrity portraits for which the artist is best known. These personal photos chronicled Leibovitz's long relationship with Sontag. They featured many pictures of the author, including some showing her battle with cancer, her treatment, and ultimately her death and burial.

In an interview in The Guardian in 2000, Sontag was quite open about her bisexuality:[8]

"Shall I tell you about getting older?", she says, and she is laughing. "When you get older, 45 plus, men stop fancying you. Or put it another way, the men I fancy don't fancy me. I want a young man. I love beauty. So what's new?" She says she has been in love seven times in her life, which seems quite a lot. "No, hang on," she says. "Actually, it's nine. Five women, four men."

Many of Sontag's obituaries failed to mention her significant same-sex relationships, most notably that with photographer Annie Leibovitz. In response to this criticism, The New York Times' Public Editor, Daniel Okrent, defended the newspaper's obituary, stating that at the time of Sontag's death, a reporter could make no independent verification of her romantic relationship with Leibovitz (despite attempts to do so). After Sontag's death, Newsweek published an article about Leibovitz that made clear reference to her decade-plus relationship with Sontag, stating: "The two first met in the late '80s, when Leibovitz photographed her for a book jacket. They never lived together, though they each had an apartment within view of the other's."[9]

Sontag was quoted by Editor-in-Chief Brendan Lemon of Out magazine as saying "I grew up in a time when the modus operandi was the 'open secret'. I'm used to that, and quite OK with it. Intellectually, I know why I haven't spoken more about my sexuality, but I do wonder if I haven't repressed something there to my detriment. Maybe I could have given comfort to some people if I had dealt with the subject of my private sexuality more, but it's never been my prime mission to give comfort, unless somebody's in drastic need. I'd rather give pleasure, or shake things up."

Annie Leibovitz's recent exhibit of work in Washington, D.C. at the Corcoran Gallery of Art included numerous personal photos, in addition to the celebrity portraits for which the artist is best known. These personal photos chronicled Leibovitz's long relationship with Sontag. They featured many pictures of the author, including some showing her battle with cancer, her treatment, and ultimately her death and burial.

Sontag Susan Rosenblatt néven született New Yorkban, 1933. január 16-án, zsidó családban. Apja kereskedő volt, aki 1938-ban egy kínai útja során tüdőbajban meghalt. Hét évvel később anyja hozzáment Nathan Sontaghoz; Susan és húga Judith felvette mostohaapjuk nevét. Sontag az Arizona állambeli Tucsonban, majd Los Angelesben nevelkedett. Egyetemi tanulmányait a Berkley Egyetemen kezdte, de menet közben átiratkozott a University of Chicagora. Később filozófiát, irodalomtudományt és teológiát tanult a Harvardon, Oxfordban és a Sorbonne-on.

17 évesen tíz napos udvarlás után hozzáment Philip Rieffhez. Nyolc éves házasságuk alatt született egy fiuk, David. Élete során mind nőkkel, mind férfiakkal élt szerelmi viszonyban. Egy 2000-es beszélgetésben[1] azt állította, kilencszer volt életében szerelmes, ebből négy esetben nőbe és öt esetben férfiba. Élete utolsó 15 évében Annie Leibovitz fotóművésszel élt szerelmi kapcsolatban.[2]

71 évesen, 2004. december 28-án leukémiában halt meg. A párizsi Montparnasse temetőben helyezték végső nyugalomra.

17 évesen tíz napos udvarlás után hozzáment Philip Rieffhez. Nyolc éves házasságuk alatt született egy fiuk, David. Élete során mind nőkkel, mind férfiakkal élt szerelmi viszonyban. Egy 2000-es beszélgetésben[1] azt állította, kilencszer volt életében szerelmes, ebből négy esetben nőbe és öt esetben férfiba. Élete utolsó 15 évében Annie Leibovitz fotóművésszel élt szerelmi kapcsolatban.[2]

71 évesen, 2004. december 28-án leukémiában halt meg. A párizsi Montparnasse temetőben helyezték végső nyugalomra.

.jpg)

Nincsenek megjegyzések:

Megjegyzés küldése