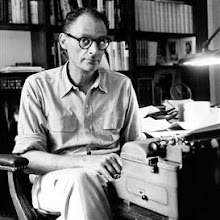

Ephraim Kishon (Hebrew: אפרים קישון, August 23, 1924 – January 29, 2005) was an Israeli writer, satirist, dramatist, screenwriter, and film director.

Ephraim Kishon (Hebrew: אפרים קישון, August 23, 1924 – January 29, 2005) was an Israeli writer, satirist, dramatist, screenwriter, and film director.Born into a middle-class Jewish family in Budapest, Hungary, as Ferenc Hoffmann (Hungarian Hoffmann Ferenc), Kishon studied sculpture and painting, and then began publishing humorous essays and writing for the stage.

During World War II the Nazis imprisoned him in several concentration camps. At one camp his chess talent helped him survive as the camp commandant was looking for an opponent. In another camp the Germans lined up the inmates shooting every tenth person, passing him by. He later wrote in his book The Scapegoat, "They made a mistake—they left one satirist alive." He managed to escape while being transported to the Sobibor death camp in Poland, and hid the remainder of the war disguised as "Stanko Andras", a Slovakian laborer.

After 1945 he changed his surname from Hoffmann to Kishont to disguise his Jewish heritage and returned to Hungary to study art and publish humorous plays. He immigrated to Israel in 1949 to escape the Communist regime, and an immigration officer gave him the name Ephraim Kishon.

His first marriage, in 1946 to Eva (Chawa) Klamer, ended in divorce. In 1959, he married his second wife Sara (née Lipovitz), who died in 2002. In 2003, he married the Austrian writer Lisa Witasek. He had three children: Raphael (b. 1957), Amir (b. 1963), and Renana (b. 1968).

Acquiring a mastery of Hebrew with remarkable speed, Kishon started a regular satirical column in the easy-Hebrew daily, Omer, after two years in the country. From 1952, he wrote the column "Had Gadya" in the daily Ma'ariv. Devoted largely to political and social satire but including essays of pure humour, it became one of the most popular columns in the country. His extraordinary inventiveness, both in the use of language and the creation of character, was applied also to the writing of innumerable sketches for theatrical revues.

Collections of his humorous writings have appeared in Hebrew and in translation. Among the English translations are Look Back Mrs. Lot (1960), Noah's Ark, Tourist Class (1962), The Seasick Whale (1965), and two books on the Six-Day War and its aftermath, So Sorry We Won (1967), and Woe to the Victors (1969). Two collections of his plays have also appeared in Hebrew: Shemo Holekh Lefanav (1953) and Ma´arkhonim (1959).

His works have been translated into 37 languages, the majority of which were sold in Germany. Kishon rejected the idea of universal guilt for the Holocaust and had many friends in Germany. Kishon said “It gives me great satisfaction to see the grandchildren of my executioners queuing up to buy my books.” Friedrich Torberg was his congenial translator to German, until he died in 1979; thereafter Kishon himself wrote in German. Ultimately, he wrote over 50 books.

Kishon was a life-long chess enthusiast, and took an early interest in chess-playing computers. In 1990, German chess computer manufacturer Hegener & Glaser together with Fidelity produced the Kishon Chesster, a chess computer distinguished by the spoken comments it would make during a game. Kishon wrote the comments to be humorous, but were also carefully chosen to be relevant to chess and the position in the game.

In 1981, Kishon established a second home in the rural Swiss canton of Appenzell. He had come to feel somewhat estranged and unappreciated in Israel, believing that some native-born Israelis were against him because he was a Hungarian immigrant and that the literary establishment looked down on his best-selling "middle-brow" works. Kishon became increasingly conservative and continued to strongly support Zionism.

Kishon died in Switzerland at age 80, apparently of a heart attack. His body was returned to Israel and buried in the artists' cemetery in Tel Aviv.

Rosszkor és rossz helyen, az 1920-as években Magyarországon született Hoffmann (később Kishont) Ferenc. Zsidó bankár gyermekeként nem mehetett egyetemre. A zsidótörvények árnyékában ötvösnek tanult, majd Budapest erődítésein dolgozott, ahogyan nyilas őrei mondták: "a bolsevik pestis megfékezésén". Amikor a front elérte a város határát, megszökött, majd két hetet töltött a magyar–német és az orosz frontvonalak között egy pincében, paradicsomlén élve. Ekkor írta Hajvédők című regényét, amelyért díjat is kapott.

Rosszkor és rossz helyen, az 1920-as években Magyarországon született Hoffmann (később Kishont) Ferenc. Zsidó bankár gyermekeként nem mehetett egyetemre. A zsidótörvények árnyékában ötvösnek tanult, majd Budapest erődítésein dolgozott, ahogyan nyilas őrei mondták: "a bolsevik pestis megfékezésén". Amikor a front elérte a város határát, megszökött, majd két hetet töltött a magyar–német és az orosz frontvonalak között egy pincében, paradicsomlén élve. Ekkor írta Hajvédők című regényét, amelyért díjat is kapott. A felszabadulást követően a Ludas Matyi munkatársa lett, majd búcsút mondott a lapnak és hazájának is. Bécsből küldte el a szerkesztőségnek a következő üzenetet: "Üdvözlet a szabad Magyarországnak, a szabad Kishonttól!"

Izraelbe emigrált, ahol rövid időn belül ráébredt, hogy a kibuc közösségi életét nem neki találták ki. Ez a ráébredés kölcsönös volt, ahonnan a héber nyelvet már egészen jól beszélő Efraim Kishon (már t nélkül) Tel-Avivba ment. Újságírással foglalkozott, maró és éles stílusú írásaiban görbe tükröt tartott az éppen formálódó izraeli társadalom elé. Az 1967-es, hatnapos háborút követően megjelent kötete, amely a "Bocsánat, hogy győztünk!" címet viselte, s a külvilág reakcióit parodizálta.

Tíz éven keresztül Hollywoodban lakott, ahol forgatókönyveket írt és rendezett. Tel-Avivban saját kabaréja is volt. Hosszabb időn keresztül élt Svájcban élt, a halál is itt érte utol.

Házasságlevél című darabját néhány évvel ezelőtt a budapesti József Attila Színház mutatta be. Szatíráiból és humoreszkjeiből több válogatáskötet jelent meg Magyarországon.

Nyolc évtizedet élt, gyermekei és unokái mellett a humort kedvelő rajongók tömegei is érezni fogják hiányát. Hogy mennyire képtelennek érezték halálhírét, arra gyermekének, Rafinak szavai voltak a legtalálóbbak: "Amikor megérkezett a holttestét szállító gép Svájcból, arra gondoltam, hogy amint kinyílik az ajtaja, ott fog állni apa, mosolyog és annyit mond: »Csak kíváncsi voltam, mennyire szerettek!«"

.jpg)

Nincsenek megjegyzések:

Megjegyzés küldése