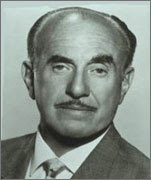

Sheldon Gary Adelson (born August 1, 1933)[1] is an American billionaire businessman. He is a property developer and public company CEO based in Las Vegas, Nevada.

Sheldon Gary Adelson (born August 1, 1933)[1] is an American billionaire businessman. He is a property developer and public company CEO based in Las Vegas, Nevada.Adelson is Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of the Las Vegas Sands Corp., the parent company of Venetian Macao Limited which operates The Venetian Resort Hotel Casino and the Sands Expo and Convention Center. Adelson vastly increased his net worth upon the initial public offering of Las Vegas Sands (NYSE: LVS) in December 2004 by selling just 10% of the shares. With an estimated wealth of US$26.5 bn, he is the United States' third richest person as of 2007[2].

Adelson has most recently come under fire for his close involvement with the 527 lobbying group Freedom's Watch, which has unsucessfully financed several Republican congressional candidates and had intended to raise as much as $250 million to attack Barack Obama's presidential campaign.[3] Adelson has also been criticized for aggressive union busting against employees of his Las Vegas casino properties.[4]

Adelson has also been accused of pursuing "despicable business practices" and having "habitually and corruptly bought political favour" by the conservative Daily Mail of London, although Adelson successfully sued the newspaper for libel in 2008.

As of 2008 Adelson was reported to be in poor health, relying on a cane to walk.

Adelson's parents were Jewish. His mother's family emigrated to the United States from Ukraine; his father's family came from Lithuania[6] Adelson was born and grew up in the Dorchester neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts, a rough-and-tumble section of Boston, where his father drove a taxicab. [7]

He worked at a young age selling newspapers on local street corners and owned his first business by the time he was twelve. In the years that followed, he worked as a mortgage broker, investment adviser and financial consultant. He started a business selling toiletry kits, and in the 1960s he started a charter tours business with two friends. [7] He went to college at City College of New York but did not complete a degree there.

He worked at a young age selling newspapers on local street corners and owned his first business by the time he was twelve. In the years that followed, he worked as a mortgage broker, investment adviser and financial consultant. He started a business selling toiletry kits, and in the 1960s he started a charter tours business with two friends. [7] He went to college at City College of New York but did not complete a degree there.

The basis for Adelson's wealth and current investments was the computer trade show COMDEX, which he and his partners developed for the computer industry; the first show was in 1979. It was the premier computer trade show through much of the 1980s and 1990s.[7]

The basis for Adelson's wealth and current investments was the computer trade show COMDEX, which he and his partners developed for the computer industry; the first show was in 1979. It was the premier computer trade show through much of the 1980s and 1990s.[7]In 1988, Adelson and his partners purchased the Sands Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas, Nevada, the former hangout of Frank Sinatra and the Rat Pack, in order to bring Las Vegas to a new phase of business centricity through the exhibition industry. The following year, Adelson and his partners constructed the Sands Expo and Convention Center, the only privately owned and operated convention center in the United States.

In 1991, while honeymooning in Venice with his wife Miriam (a physician), Adelson said he found the inspiration for a mega-resort hotel. He razed (by implosion) the venerable Sands and spent $1.5-billion to construct the The Venetian, a Venice-themed resort hotel and casino. The luxurious, all-suite Venetian revolutionized the Las Vegas hotel industry, and has been honored with architectural and other awards naming it as one the finest hotels in the world. In 2003, The Venetian added the 1,013-suite Venezia tower - giving The Venetian 4,049 suites, 18 leading-chef restaurants, a shopping mall with canals, gondolas and singing gondoliers.

In 1995, Adelson and his partners sold the Interface Group Show Division, including the COMDEX shows, to SoftBank Corporation of Japan for $862 million; Adelson's share was just over $500 million.[7]

Adelson spearheaded a major project to bring the Sands name to the Macao SAR, China, the Chinese gambling city that was a Portuguese colony until December 1999. The one million-square-foot Sands Macau became the People's Republic of China's first Las Vegas-style casino when it opened in May 2004.

In May 2006, Adelson's Las Vegas Sands was awarded a hotly contested license to construct a casino resort in Singapore's Marina Bay. The new casino is expected to open in 2009 at a rumored cost of $3.16 billion.

In August 2007, Adelson opened the $2.4 billion Venetian Macao Resort Hotel on Cotai and announced that he planned to create a massive, concentrated resort area he called the Cotai Strip, after its Las Vegas counterpart. Adelson said that he planned to open more hotels under brands such as Four Seasons, Sheraton and St. Regis. His Las Vegas Sands plans to invest $12 billion and build 20,000 hotel rooms on the Cotai Strip by 2010.[8]

In September 2007, Adelson announced that the Sands would open its second hotel, the Sands Macao Hotel in Macau in October of that year.[9]

In 2007, Adelson made an unsuccessful bid to buy controlling interest in the Israeli newspaper Maariv. When this failed, he proceeded with parallel plans to publish a free daily newspaper to compete with Israeli, a newspaper he had co-founded in 2006 but had left. [10] The first edition of the new newspaper, Israel HaYom, was published on July 30, 2007.

In March 2008, Adelson won a ₤4 million judgement against the Daily Mail, for libel. He had been accused of "despicable business practices" and "habitually and corruptly bought political favour". Adelson said he would donate the damages to the Royal Marsden cancer hospital in London.

Since 1991, Adelson has been married to Miriam Ochshorn, a physician who works with drug addicts.[12] Adelson fathered at least two sons, Mitchell and Gary. Both of Adelson's sons have struggled with drug addiction, Mitchell dying from an overdose in 2005.

Adelson currently has funded over $25 million to the M.I.S. Hebrew Academy in Las Vegas to build a high school. Currently, the high school has a 9th and 10th grade and will add more grades annually.

In 2005, Adelson was among 53 entities that contributed the maximum of $250,000 to the second inauguration of President George W. Bush.[13] [14] [15]

In 2006 Adelson contributed $25 million to the organization Birthright Israel, which finances Jewish youth trips to Israel. The gift is anticipated to be given annually for the foreseeable future [16]

In 2007 Adelson founded Freedom's Watch, a group that advocates America's continued involvement in the war in Iraq, and is run and supported, in part, by former officials of the Bush administration. Also in 2007, Adelson pledged another $25 million to the Birthright Israel program, allowing for approximately 20,000 people to take part in the program. [17]

Adelson also has funded the Boston based Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation. AMRF is a private foundation committed to a model of open and highly integrated collaboration among outstanding investigators who participate in goal-directed basic and clinical research to prevent, reduce or eliminate disabling and life-threatening illness. [18]

This foundation initiated the Adelson Program in Neural Repair and Rehabilitation (APNRR) with $7.5 million donated to collaborating researchers at 10 universities. [19] Adelson has publicly pledged billions to medical research and has encouraged researchers to contact AMRF with ideas that need to be funded.

Along with his wife, Dr. Miriam Adelson, Sheldon Adelson was presented with the Woodrow Wilson Award for Corporate Citizenship by the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars of the Smithsonian Institution.[20] The ceremony was held on March 25, 2008 in Las Vegas, Nevada. The other award recipient that night was Wayne Newton, who received the Woodrow Wilson Award for Public Service.

A világ legnagyobb kaszinója kétszer akkora, mint a Las Vegas-i Venetian. Az amerikai befektető szerint 2,4 milliárd dolláros befektetése 3-5 éven belül fog megtérülni. A kaszinót Sheldon Adelson amerikai milliárdos avatta fel. A kaszinó-, hotel- és szórakoztatókoplexumhoz 3000 szállodai szoba, 1150 játékasztal, 7000 nyerőautomata, 350 üzlet, egy 1800 férőhelyes konferenciaközpont és egy 15 ezer férőhelyes sportaréna is tartozik.

A világ legnagyobb kaszinója kétszer akkora, mint a Las Vegas-i Venetian. Az amerikai befektető szerint 2,4 milliárd dolláros befektetése 3-5 éven belül fog megtérülni. A kaszinót Sheldon Adelson amerikai milliárdos avatta fel. A kaszinó-, hotel- és szórakoztatókoplexumhoz 3000 szállodai szoba, 1150 játékasztal, 7000 nyerőautomata, 350 üzlet, egy 1800 férőhelyes konferenciaközpont és egy 15 ezer férőhelyes sportaréna is tartozik.

In 2005, Adelson was among 53 entities that contributed the maximum of $250,000 to the second inauguration of President George W. Bush.[13] [14] [15]

In 2006 Adelson contributed $25 million to the organization Birthright Israel, which finances Jewish youth trips to Israel. The gift is anticipated to be given annually for the foreseeable future [16]

In 2007 Adelson founded Freedom's Watch, a group that advocates America's continued involvement in the war in Iraq, and is run and supported, in part, by former officials of the Bush administration. Also in 2007, Adelson pledged another $25 million to the Birthright Israel program, allowing for approximately 20,000 people to take part in the program. [17]

Adelson also has funded the Boston based Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation. AMRF is a private foundation committed to a model of open and highly integrated collaboration among outstanding investigators who participate in goal-directed basic and clinical research to prevent, reduce or eliminate disabling and life-threatening illness. [18]

This foundation initiated the Adelson Program in Neural Repair and Rehabilitation (APNRR) with $7.5 million donated to collaborating researchers at 10 universities. [19] Adelson has publicly pledged billions to medical research and has encouraged researchers to contact AMRF with ideas that need to be funded.

Along with his wife, Dr. Miriam Adelson, Sheldon Adelson was presented with the Woodrow Wilson Award for Corporate Citizenship by the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars of the Smithsonian Institution.[20] The ceremony was held on March 25, 2008 in Las Vegas, Nevada. The other award recipient that night was Wayne Newton, who received the Woodrow Wilson Award for Public Service.

A világ legnagyobb kaszinója kétszer akkora, mint a Las Vegas-i Venetian. Az amerikai befektető szerint 2,4 milliárd dolláros befektetése 3-5 éven belül fog megtérülni. A kaszinót Sheldon Adelson amerikai milliárdos avatta fel. A kaszinó-, hotel- és szórakoztatókoplexumhoz 3000 szállodai szoba, 1150 játékasztal, 7000 nyerőautomata, 350 üzlet, egy 1800 férőhelyes konferenciaközpont és egy 15 ezer férőhelyes sportaréna is tartozik.

A világ legnagyobb kaszinója kétszer akkora, mint a Las Vegas-i Venetian. Az amerikai befektető szerint 2,4 milliárd dolláros befektetése 3-5 éven belül fog megtérülni. A kaszinót Sheldon Adelson amerikai milliárdos avatta fel. A kaszinó-, hotel- és szórakoztatókoplexumhoz 3000 szállodai szoba, 1150 játékasztal, 7000 nyerőautomata, 350 üzlet, egy 1800 férőhelyes konferenciaközpont és egy 15 ezer férőhelyes sportaréna is tartozik. 2004 májusa nagy fordulatot hozott Makaó – és a helyi szerencsejáték-ipart addig uraló milliárdos mágnás, Stanley Ho – életében: Sheldon Adelson, Las Vegas ura, a világ hatodik leggazdagabb embere negyvenezres tömeg ünneplő gyűrűjében megnyitotta első kaszinóját a városban… A 265 millió dollárból épült gigantikus Sands Casino a sziget régebbi hasonló intézményeinek a szó szoros értelmében a fejére nőtt, ezért az egyeduralomhoz szokott Ho ellencsapásként megépítette az 52 emeletes, lótuszvirág alakú Grand Lisboa kaszinót. A Makaóért folytatott küzdelem startpisztolya tehát eldördült. Vajon ki lesz a nyertese – és ki az igazi vesztese az őrült vetélkedésnek?

Átadták Macaón a világ legnagyobb kaszinóját

A Venetian Macao mintegy 2.4 milliárd dolláros beruházás, és Las Vegas valamennyi kaszinójánál nagyobb. Az új létesítményben 3,000 hotel szoba, valamint közel 550 ezer négyzetméteren 870 játékasztalt, és 3,400 darab pénznyerő automatát helyeztek el. A szórakoztató komplexumot létrehozó Las Vegas Sands, valamint fő tulajdonosa, az amerikai milliárdos, Sheldon Adelson elmondta: legnagyobb álmai közé tartozott, megépíteni a szórakoztatás fellegvárát Ázsiában az ázsiaiak számára.

A Venetian Macao mintegy 2.4 milliárd dolláros beruházás, és Las Vegas valamennyi kaszinójánál nagyobb. Az új létesítményben 3,000 hotel szoba, valamint közel 550 ezer négyzetméteren 870 játékasztalt, és 3,400 darab pénznyerő automatát helyeztek el. A szórakoztató komplexumot létrehozó Las Vegas Sands, valamint fő tulajdonosa, az amerikai milliárdos, Sheldon Adelson elmondta: legnagyobb álmai közé tartozott, megépíteni a szórakoztatás fellegvárát Ázsiában az ázsiaiak számára.

Munkához láthattak végre tegnap New Yorkban a 2001. szeptember 11-én terrortámadásban lerombolt World Trade Center (WTC) helyén létesülő emlékhely és múzeum, valamint toronyházak építői, miután a területet birtokló New York-i és New Jersey-i kikötői hatóság, valamint a bérlő, Larry Silverstein építési vállalkozó szerdán megegyezett egymással – írta az AP. A megállapodás értelmében a milliárdos üzletember – aki nem sokkal a merénylet előtt megszerezte a komplexum haszonbérleti jogát – átadta a szimbolikus jelentőségű Szabadság-torony építésének ellenőrzését az állami hivataloknak. Az elhúzódó megbeszélések többször, utoljára egy hónapja szakadtak meg, mert a New York-i hatóságok szerint Larry Silverstein rosszhiszemű magatartást tanúsított az üzleti tárgyalásokon. A vita a Szabadság-torony építése körül lángolt fel. Mint megírtuk, Silverstein elképzelése szerint a WTC helyett épülő Szabadság-torony 72 emeletes épületének hatvan szintjét irodák, tízet pedig üzletek és éttermek foglalnának el. A létesítményre a későbbiekben még négy torony felhúzását is tervezi a vállalkozó, ennek időpontját anyagi lehetőségeitől tette függővé. Mivel Silverstein havi tízmillió dollár haszonbérleti díjat fizet a területért, de még nem kapta meg a teljes biztosítási összeget, sőt költséges perek elébe néz, az állami hivatalok attól tartottak, hogy elfogy a pénze az építkezés befejezése előtt, és a díjjal is adós marad. Ezért akarták átvenni az ellenőrzést az építkezés fölött. A mostani egyezség szerint a milliárdos az emlékhelyet körülvevő öt felhőkarcolóból négyet – köztük a Szabadság-tornyot – húzhat fel, míg a New York-i és New Jersey-i kikötői hatóság egyet. Silverstein a négyből két toronyház építésének ellenőrzését adta át a tulajdonosnak. Ha minden jól megy, akkor a munkákkal 2012-re végezhetnek. Larry Silverstein a 2001. szeptember 11-i merénylet előtt két hónappal szerezte meg a terület és az épületek bérleti jogát 99 évre. A szerencsétlenség után 4,6 milliárd dollár kártérítést ítéltek neki.

Munkához láthattak végre tegnap New Yorkban a 2001. szeptember 11-én terrortámadásban lerombolt World Trade Center (WTC) helyén létesülő emlékhely és múzeum, valamint toronyházak építői, miután a területet birtokló New York-i és New Jersey-i kikötői hatóság, valamint a bérlő, Larry Silverstein építési vállalkozó szerdán megegyezett egymással – írta az AP. A megállapodás értelmében a milliárdos üzletember – aki nem sokkal a merénylet előtt megszerezte a komplexum haszonbérleti jogát – átadta a szimbolikus jelentőségű Szabadság-torony építésének ellenőrzését az állami hivataloknak. Az elhúzódó megbeszélések többször, utoljára egy hónapja szakadtak meg, mert a New York-i hatóságok szerint Larry Silverstein rosszhiszemű magatartást tanúsított az üzleti tárgyalásokon. A vita a Szabadság-torony építése körül lángolt fel. Mint megírtuk, Silverstein elképzelése szerint a WTC helyett épülő Szabadság-torony 72 emeletes épületének hatvan szintjét irodák, tízet pedig üzletek és éttermek foglalnának el. A létesítményre a későbbiekben még négy torony felhúzását is tervezi a vállalkozó, ennek időpontját anyagi lehetőségeitől tette függővé. Mivel Silverstein havi tízmillió dollár haszonbérleti díjat fizet a területért, de még nem kapta meg a teljes biztosítási összeget, sőt költséges perek elébe néz, az állami hivatalok attól tartottak, hogy elfogy a pénze az építkezés befejezése előtt, és a díjjal is adós marad. Ezért akarták átvenni az ellenőrzést az építkezés fölött. A mostani egyezség szerint a milliárdos az emlékhelyet körülvevő öt felhőkarcolóból négyet – köztük a Szabadság-tornyot – húzhat fel, míg a New York-i és New Jersey-i kikötői hatóság egyet. Silverstein a négyből két toronyház építésének ellenőrzését adta át a tulajdonosnak. Ha minden jól megy, akkor a munkákkal 2012-re végezhetnek. Larry Silverstein a 2001. szeptember 11-i merénylet előtt két hónappal szerezte meg a terület és az épületek bérleti jogát 99 évre. A szerencsétlenség után 4,6 milliárd dollár kártérítést ítéltek neki.

Abrams then collaborated with producer

Abrams then collaborated with producer  Jeffrey Jacob Abrams (névváltozatai még Jeffrey Abrams vagy J. J. Abrams) (

Jeffrey Jacob Abrams (névváltozatai még Jeffrey Abrams vagy J. J. Abrams) (

Lukács (Löwinger) György Bernát (

Lukács (Löwinger) György Bernát (

Jacques Derrida (

Jacques Derrida (

.jpg)