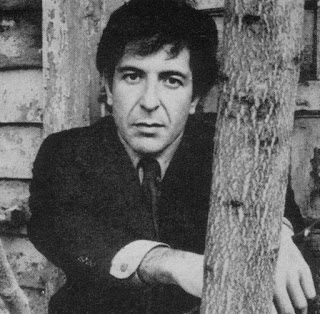

Leonard Norman Cohen, CC (born September 21, 1934 in Westmount, Montreal, Quebec) is a Canadian singer-songwriter, poet and novelist. Cohen published his first book of poetry in Montreal in 1956 and his first novel in 1963.

Leonard Norman Cohen, CC (born September 21, 1934 in Westmount, Montreal, Quebec) is a Canadian singer-songwriter, poet and novelist. Cohen published his first book of poetry in Montreal in 1956 and his first novel in 1963.Cohen's earliest songs (many of which appeared on the 1968 album Songs of Leonard Cohen) were rooted in European folk music melodies and instrumentation, sung in a high baritone. The 1970s were a musically restless period in which his influences broadened to encompass pop, cabaret, and world music. Since the 1980s he has typically sung in lower registers (bass baritone, sometimes bass), with accompaniment from electronic synthesizers and female backing singers.

His work often explores the themes of religion, isolation, sexuality, and complex interpersonal relationships.

Cohen's songs and poetry have influenced many other singer-songwriters, and more than a thousand renditions of his work have been recorded. He has been inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame and the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame and is also a Companion of the Order of Canada, the nation's highest civilian honour. Cohen will be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame on March 10, 2008 for his status among the "highest and most influential echelon of songwriters".

Cohen was born to a middle-class Jewish family of Polish-Lithuanian ancestry in 1934 in Montreal, Quebec. He grew up in Westmount on the Island of Montreal. His father, Nathan Cohen, was the owner of a substantial Montreal clothing store, and died when Leonard was nine years old. Like many other Jews named Cohen, Katz, Kagan, etc., his family made a claim of descent from the Kohanim: "I had a very Messianic childhood," he told Richard Goldstein in 1967. "I was told I was a descendant of Aaron, the high priest."[2] As a teenager he learned to play the guitar, subsequently forming a country-folk group called the Buckskin Boys. His father's will provided Leonard with a modest trust income, sufficient to allow him to pursue his literary ambitions.

In 1967, Cohen relocated to the United States to pursue a career as a folk singer-songwriter. His song "Suzanne" became a hit for Judy Collins. After performing at a few folk festivals, he came to the attention of Columbia Records representative John H. Hammond (who signed artists such as Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, and Billie Holiday).

The sound of Cohen's first album Songs of Leonard Cohen (1967) was too dark to be a commercial success, but was widely acclaimed by folk music buffs. He became a cult name in the UK, where the album spent over a year on the album charts. He followed up with Songs from a Room (1969) (featuring the oft-covered "Bird on the Wire"), Songs of Love and Hate (1971), Live Songs (1973), and New Skin for the Old Ceremony (1974).

In 1971, Cohen's music was used to great effect in the soundtrack to Robert Altman's film 'McCabe & Mrs. Miller'. Though pulled from the existing Cohen catalog, the songs melded so seamlessly with the story that many believed they had been written for the film.

Throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s, Cohen toured the United States, Canada and Europe. In 1973, Cohen toured Israel and performed at army bases during the Yom Kippur War. Beginning around 1974, his collaboration with pianist/arranger John Lissauer created a live sound praised by the critics, but which was never really captured on record. During this time, Cohen often toured with Jennifer Warnes as a back-up singer. Warnes would become a fixture on Cohen's future albums and she recorded an album of Cohen songs in 1987, Famous Blue Raincoat.

In 1977, Cohen released Death of a Ladies' Man (note the plural possessive case; one year later in 1978, Cohen released a volume of poetry with the coyly revised title, Death of a Lady's Man). The album was produced by Phil Spector, well known as the inventor of the "wall of sound" technique, in which pop music is backed with thick layers of instrumentation, an approach very different from Cohen's usually minimalist instrumentation. The recording of the album was fraught with difficulty; Spector reportedly mixed the album in secret studio sessions and Cohen said Spector once threatened him with a crossbow. Cohen thinks the end result is "grotesque",[3] but also "semi-virtuous".[4]

In 1979, Cohen returned with the more traditional Recent Songs. Produced by Cohen himself and Henry Lewy (Joni Mitchell's sound engineer) the album included performances by a jazz-fusion band introduced to Cohen by Mitchell and oriental instruments (oud, Gypsy violin and mandolin). In 2001 Cohen released the live version of songs from his 1979 tour, Field Commander Cohen: Tour of 1979.

The sound of Cohen's first album Songs of Leonard Cohen (1967) was too dark to be a commercial success, but was widely acclaimed by folk music buffs. He became a cult name in the UK, where the album spent over a year on the album charts. He followed up with Songs from a Room (1969) (featuring the oft-covered "Bird on the Wire"), Songs of Love and Hate (1971), Live Songs (1973), and New Skin for the Old Ceremony (1974).

In 1971, Cohen's music was used to great effect in the soundtrack to Robert Altman's film 'McCabe & Mrs. Miller'. Though pulled from the existing Cohen catalog, the songs melded so seamlessly with the story that many believed they had been written for the film.

Throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s, Cohen toured the United States, Canada and Europe. In 1973, Cohen toured Israel and performed at army bases during the Yom Kippur War. Beginning around 1974, his collaboration with pianist/arranger John Lissauer created a live sound praised by the critics, but which was never really captured on record. During this time, Cohen often toured with Jennifer Warnes as a back-up singer. Warnes would become a fixture on Cohen's future albums and she recorded an album of Cohen songs in 1987, Famous Blue Raincoat.

In 1977, Cohen released Death of a Ladies' Man (note the plural possessive case; one year later in 1978, Cohen released a volume of poetry with the coyly revised title, Death of a Lady's Man). The album was produced by Phil Spector, well known as the inventor of the "wall of sound" technique, in which pop music is backed with thick layers of instrumentation, an approach very different from Cohen's usually minimalist instrumentation. The recording of the album was fraught with difficulty; Spector reportedly mixed the album in secret studio sessions and Cohen said Spector once threatened him with a crossbow. Cohen thinks the end result is "grotesque",[3] but also "semi-virtuous".[4]

In 1979, Cohen returned with the more traditional Recent Songs. Produced by Cohen himself and Henry Lewy (Joni Mitchell's sound engineer) the album included performances by a jazz-fusion band introduced to Cohen by Mitchell and oriental instruments (oud, Gypsy violin and mandolin). In 2001 Cohen released the live version of songs from his 1979 tour, Field Commander Cohen: Tour of 1979.

Leonard Norman Cohen (Montréal, 1934. szeptember 21.) kanadai költő, regényíró, énekes és dalszövegíró.

Leonard Norman Cohen (Montréal, 1934. szeptember 21.) kanadai költő, regényíró, énekes és dalszövegíró.Cohen egy lengyel eredetű középosztálybeli zsidó családba született 1934-ben a québeci Montréalban és Westmountban nőtt fel. Apja, Nathan Cohen, aki tehetős üzletember, egy montréali ruházati bolt vállalkozás tulajdonosa volt, meghalt Leonard kilenc éves korában. Családja, mint a legtöbb Cohen, Kohn, Katz, Kagan stb. nevű zsidó család, a kohaniták leszármazottjának tartotta magát: "Nagyon messianisztikus gyerekkorom volt", mondta 1967-ben. "Azt mondták, hogy Áron főpap leszármazottja vagyok."[1] Tizenévesen tanult meg gitározni, majd alapított egy country-folk együttest Buckskin Boys néven. Apja végrendelete értelmében rendszeres szerény jövedelemhez jutott, ami lehetővé tette, hogy irodalmi ambícióinak élhessen.

1951-ben beiratkozott a McGill Egyetemre, ahol a McGilli Szónoki Egyesület elnöke lett. Első verseskötete még egyetemi évei alatt, 1956-ban jelent meg Let Us Compare Mythologies címmel. 1961-ben kiadott második kötete, a The Spice-Box of Earth tette ismertté nevét irodalmi körökben, elsősorban Kanadában.

Cohen szigorú munkafegyelem szerint dolgozott korai szenvedélyes korszakában. A hatvanas években verseket és prózát is írt, és meglehetősen visszavonultan élt. Egy görög szigetre, Idrára költözött, itt írta Flowers for Hitler című verseskötetét (1964), valamint a The Favourite Game (1963) és Beautiful Losers (1966) című regényeit, amelyek azóta magyarul is megjelentek (A kedvenc játék; Szépséges lúzerek).

A kedvenc játék egy önéletrajzi tárgyú bildungsroman, nevelési regény egy fiatalemberről, aki az írásban találja meg önmagát. Ezzel szemben a Szépséges lúzereket ellen-bildungsromannak tekinthetjük, hiszen – korai posztmodern mintára – a szentet a profánnal, a vallást a szexualitással vegyítve vizsgálja a főszereplők önazonosságát gazdag, lírai nyelvezetben. A regényben Cohen québeci gyökerei is megjelennek – bár ez egy zsidó hátterű szerzőtől talán kissé szokatlan – , az egyik mellékszál egy katolikus boldogról, az irokéz indián Kateri Tekakwitháról szól. A Szépséges lúzerek kezdetben megdöbbentette a kanadai kritikusokat szókimondó szexuális tartalma miatt.

Cohen szigorú munkafegyelem szerint dolgozott korai szenvedélyes korszakában. A hatvanas években verseket és prózát is írt, és meglehetősen visszavonultan élt. Egy görög szigetre, Idrára költözött, itt írta Flowers for Hitler című verseskötetét (1964), valamint a The Favourite Game (1963) és Beautiful Losers (1966) című regényeit, amelyek azóta magyarul is megjelentek (A kedvenc játék; Szépséges lúzerek).

A kedvenc játék egy önéletrajzi tárgyú bildungsroman, nevelési regény egy fiatalemberről, aki az írásban találja meg önmagát. Ezzel szemben a Szépséges lúzereket ellen-bildungsromannak tekinthetjük, hiszen – korai posztmodern mintára – a szentet a profánnal, a vallást a szexualitással vegyítve vizsgálja a főszereplők önazonosságát gazdag, lírai nyelvezetben. A regényben Cohen québeci gyökerei is megjelennek – bár ez egy zsidó hátterű szerzőtől talán kissé szokatlan – , az egyik mellékszál egy katolikus boldogról, az irokéz indián Kateri Tekakwitháról szól. A Szépséges lúzerek kezdetben megdöbbentette a kanadai kritikusokat szókimondó szexuális tartalma miatt.

1967-ben Cohen az Egyesült Államokba költözött, hogy megkezdje folk-rock énekesi és dalszerzői pályafutását. Fellépett egy pár fesztiválon, ekkor figyelt fel rá a Columbia Records képviselője, John H. Hammond, aki olyan művészek producere volt, mint Billie Holiday, Bob Dylan és Bruce Springsteen.

Suzanne című dalát először Judy Collins vitte sikerre, majd Cohen maga is elénekelte első albumán, a '67-ben megjelent Songs of Leonard Cohenen. Az album sötét hangvétele miatt nem kelt el túl nagy példányszámban, de a folkrajongók körében nagy sikert aratott. Az Egyesült Királyságban több mint egy évet töltött a lemezeladási listákon. Ezt több hasonló album követte: Songs from a Room (1969) (rajta egyik legtöbbször feldolgozott dala, a Bird on the Wire), Songs of Love and Hate (1971) és New Skin for the Old Ceremony (1974).

A 60-as években és a 70-es évek elején Cohen bejárta az Egyesült Államokat, Kanadát és Európát. 1973-ban Izraelben turnézott és katonai állomásokon is fellépett a jom kippuri háború során. 1974-től kezdve együtt koncertezett John Lissauer zongoristával, közös munkájukat a kritika is elismerte, de hangfelvétel sosem készült róla. Ekkoriban Cohen koncertjein már gyakran vokálozott Jennifer Warnes, aki állandó közreműködő lett a későbbi albumokon (ő énekli például a női szólamot a Take This Waltzban). Warnes 1987-ben saját neve alatt is kiadott egy Cohen-feldolgozásokat tartalmazó lemezt Famous Blue Raincoat címmel.

1977-ben jelent meg a Death of a Ladies' Man című lemez, melynek producere Phil Spector volt, akit a "wall of sound" technika feltalálójaként ismernek. A lemezen a popzene gazdag hangszereléssel párosul, ami nagyban eltér Cohen addig megszokott minimalista stílusától. A felvételeket sok nehézség kísérte; Spector állítólag titokban keverte az albumot és egyszer fegyverrel fenyegette meg Cohent. Cohen kezdetben groteszknek minősítette közös munkájukat, [2] később azonban már "félig-meddig művészinek" nevezte azt.[3]

1979-ben Cohen a hagyományosabb hangvételű Recent Songsszal tért vissza. A producerek maga Cohen és Henry Lewy voltak, a lemezen megszólal egy jazz fusion együttes és egzotikus hangszerek is (úd, cigányhegedű, mandolin). A lemezbemutató turnén készült felvételek 2001-ben jelentek meg Field Commander Cohen: Tour of 1979 címmel.

Suzanne című dalát először Judy Collins vitte sikerre, majd Cohen maga is elénekelte első albumán, a '67-ben megjelent Songs of Leonard Cohenen. Az album sötét hangvétele miatt nem kelt el túl nagy példányszámban, de a folkrajongók körében nagy sikert aratott. Az Egyesült Királyságban több mint egy évet töltött a lemezeladási listákon. Ezt több hasonló album követte: Songs from a Room (1969) (rajta egyik legtöbbször feldolgozott dala, a Bird on the Wire), Songs of Love and Hate (1971) és New Skin for the Old Ceremony (1974).

A 60-as években és a 70-es évek elején Cohen bejárta az Egyesült Államokat, Kanadát és Európát. 1973-ban Izraelben turnézott és katonai állomásokon is fellépett a jom kippuri háború során. 1974-től kezdve együtt koncertezett John Lissauer zongoristával, közös munkájukat a kritika is elismerte, de hangfelvétel sosem készült róla. Ekkoriban Cohen koncertjein már gyakran vokálozott Jennifer Warnes, aki állandó közreműködő lett a későbbi albumokon (ő énekli például a női szólamot a Take This Waltzban). Warnes 1987-ben saját neve alatt is kiadott egy Cohen-feldolgozásokat tartalmazó lemezt Famous Blue Raincoat címmel.

1977-ben jelent meg a Death of a Ladies' Man című lemez, melynek producere Phil Spector volt, akit a "wall of sound" technika feltalálójaként ismernek. A lemezen a popzene gazdag hangszereléssel párosul, ami nagyban eltér Cohen addig megszokott minimalista stílusától. A felvételeket sok nehézség kísérte; Spector állítólag titokban keverte az albumot és egyszer fegyverrel fenyegette meg Cohent. Cohen kezdetben groteszknek minősítette közös munkájukat, [2] később azonban már "félig-meddig művészinek" nevezte azt.[3]

1979-ben Cohen a hagyományosabb hangvételű Recent Songsszal tért vissza. A producerek maga Cohen és Henry Lewy voltak, a lemezen megszólal egy jazz fusion együttes és egzotikus hangszerek is (úd, cigányhegedű, mandolin). A lemezbemutató turnén készült felvételek 2001-ben jelentek meg Field Commander Cohen: Tour of 1979 címmel.

George Gershwin (

George Gershwin (

Benedictus (Baruch) Spinoza (

Benedictus (Baruch) Spinoza (

.jpg)

.jpg)