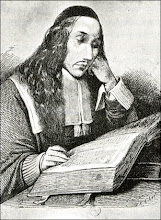

Moses Maimonides, also known as Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon or the acronym the Rambam (Hebrew: רבי משה בן מימון; Hebrew acronym: רמב"ם; (Arabic: موسى ابن ميمون Mūsā ibn Maymūn), was born in Cordoba, Spain on March 30, 1135, and died in Egypt on December 13, 1204.[5][6].

Moses Maimonides, also known as Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon or the acronym the Rambam (Hebrew: רבי משה בן מימון; Hebrew acronym: רמב"ם; (Arabic: موسى ابن ميمون Mūsā ibn Maymūn), was born in Cordoba, Spain on March 30, 1135, and died in Egypt on December 13, 1204.[5][6]. One of the greatest Torah scholars of all time, he was a rabbi, physician, and philosopher in Spain, Morocco and Egypt during the Middle Ages. He was the preeminent medieval Jewish philosopher. With the contemporary Muslim sage Averroes, he promoted and developed the philosophical tradition of Aristotle. As a result, Maimonides and Averroes would gain a prominent and controversial influence in the West, where Aristotelian thought had been suppressed for centuries. Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas were notable Western readers of Maimonides.

One of the central tenets of Maimonides's philosophy is that it is impossible for the truths arrived at by human intellect to contradict those revealed by God. Maimonides held to a strictly apophatic theology in which only negative statements toward a description of God may be considered correct. Thus, one does not say "God is One", but rather, "God is not multiple". Although many of his ideas met with the opposition of his contemporaries, Maimonides was embraced by later Jewish thinkers. The fourteen-volume Mishneh Torah today retains canonical authority as a codification of Talmudic law.

Although his copious works on Jewish law and ethics were initially met with opposition during his lifetime, he was posthumously acknowledged to be one of the foremost rabbinical arbiters and philosophers in Jewish history. Today, his works and his views are considered a cornerstone of Jewish thought and study.

Maimonides was born in 1135 in Córdoba, in present Spain. His year of birth is disputed, with Shlomo Pines suggesting that he was born in 1138. He was born during what some scholars consider to be the end of the golden age of Jewish culture in Spain, after the first centuries of the Moorish rule. At an early age, he developed an interest in the exact sciences and philosophy. In addition to reading the works of Muslim scholars, he also read those of the Greek philosophers made accessible through Arabic translations. Maimonides was not known as a supporter of mysticism. He voiced opposition to poetry, the best of which he declared as false, since it was founded on pure invention - and this too in a land which had produced such noble expressions of the Hebrew and Arabic muse. This Sage, who was revered for his saintly personality as well as for his writings, led an unquiet life, and wrote many of his works while travelling or in temporary accommodation. Maimonides studied Torah under his father Maimon, who had in turn studied under Rabbi Joseph ibn Migash.

The Almohades from Africa conquered Córdoba in 1148, and threatened the Jewish communityconversion to Islam, death, or exile with the choice of . Maimonides's family, along with most other Jews, chose exile. For the next ten years they moved about in southern Spain, avoiding the conquering Almohades, but eventually settled in Fez in Morocco, where Maimonides acquired most of his secular knowledge, studying at the University of Al Karaouine.[citation needed] During this time, he composed his acclaimed commentary on the Mishnah in the years 1166-1168.

Following this sojourn in Morocco, he lived briefly in the Holy Land, before settling in Fostat, Egypt, where he was physician of the Grand Vizier Alfadhil and Sultan Saladin of Egypt, and also treated Richard the Lionheart while on the Crusades.[10] He was considered to be the greatest physician of his time, being influenced by renowned Islamic thinkers such as Ibn Rushd and Al-Ghazali. He composed most of his œuvre in this last locale, including the Mishneh Torah. He died in Fostat, and was buried in Tiberias (today in Israel). His son Avraham, recognized as a great scholar, succeeded Maimonides as Nagid (head of the Egyptian Jewish community); he also took up his father's role as court physician, at the age of eighteen. He greatly honored the memory of his father, and throughout his career defended his father's writings against all critics. The office of Nagid was held by the Maimonides family for four successive generations until the end of the 14th century.

Maimonides was a devoted physician. In a famous letter, he describes his daily routine: After visiting the Sultan’s palace, he would arrive home exhausted and hungry, where "I would find the antechambers filled with gentiles and Jews ... I would go to heal them, and write prescriptions for their illnesses ... until the evening ... and I would be extremely weak."

He is widely respected in Spain and a statue of him was erected in Córdoba by the only synagogue in that city which escaped destruction, and which is no longer functioning as a Jewish house of worship but is open to the public.

Maimonides was one of the most influential figures in medieval Jewish philosophy. A popular medieval saying that also served as his epitaph states, From Moshe (of the Torah) to Moshe (Maimonides) there was none like Moshe.

Radical Jewish scholars in the centuries that followed can be characterised as "Maimonideans" or "anti-Maimonideans." Moderate scholars were eclectics who largely accepted Maimonides's Aristotelian world-view, but rejected those elements of it which they considered to contradict the religious tradition. Such eclecticism reached its height in the 14th-15th centuries.

The most rigorous medieval critique of Maimonides is Hasdai Crescas' Or Adonai. Crescas bucked the eclectic trend, by demolishing the certainty of the Aristotelian world-view, not only in religious matters, but even in the most basic areas of medieval science (such as physics and geometry). Crescas's critique provoked a number of 15th century scholars to write defenses of Maimonides. A translation of Crescas was produced by Harry Austryn Wolfson of Harvard University, in 1929.

In his commentary on the Mishna (tractate Sanhedrin, chapter 10), Maimonides formulates his 13 principles of faith. They summarized what he viewed as the required beliefs of Judaism with regards to:

- The existence of God

- God's unity

- God's spirituality and incorporeality

- God's eternity

- God alone should be the object of worship

- Revelation through God's prophets

- The preeminence of Moses among the prophets

- God's law given on Mount Sinai

- The immutability of the Torah as God's Law

- God's foreknowledge of human actions

- Reward of good and retribution of evil

- The coming of the Jewish Messiah

- The resurrection of the dead

These principles were controversial when first proposed, evoking criticism by Rabbi Hasdai Crescas and Rabbi Joseph Albo, and were effectively ignored by much of the Jewish community for the next few centuries. ("Dogma in Medieval Jewish Thought," Menachem Kellner). However, these principles became widely held; today, Orthodox Judaism holds these beliefs to be obligatory. Two poetic restatements of these principles (Ani Ma'amin and Yigdal) eventually became canonized in the "siddur" (Jewish prayer book).

Negative theology

The principle which inspired his philosophical activity was identical with the fundamental tenet of Scholasticism: there can be no contradiction between the truths which God has revealed, and the findings of the human mind in science and philosophy. Maimonides primarily relied upon the science of Aristotle and the teachings of the Talmud, commonly finding basis in the former for the latter. In some important points, however, he departed from the teaching of Aristotle; for instance, he rejected the Aristotelian doctrine that God's provident care extends only to humanity, and not to the individual.

Maimonides was led by his admiration for the neo-Platonic commentators to maintain many doctrines which the Scholastics could not accept. For instance, Maimonides was an adherent of "negative theology" (also known as "Apophatic theology".) In this theology, one attempts to describe God through negative attributes. For instance, one should not say that God exists in the usual sense of the term; all we can safely say is that God is not non-existent. We should not say that "God is wise"; but we can say that "God is not ignorant," i.e. in some way, God has some properties of knowledge. We should not say that "God is One," but we can state that "there is no multiplicity in God's being." In brief, the attempt is to gain and express knowledge of God by describing what God is not; rather than by describing what God "is."

The Scholastics agreed with him that no predicate is adequate to express the nature of God; but they did not go so far as to say that no term can be applied to God in the affirmative sense. They admitted that while "eternal," "omnipotent," etc., as we apply them to God, are inadequate, at the same time we may say "God is eternal" etc., and need not stop, as Moses did, with the negative "God is not not-eternal," etc. In essence what Maimonides wanted to express is that when people give God anthropomorphic qualities they do not explain anything more of what God is, because we cannot know anything of the essence of God.

Maimonides' use of apophatic theology is not unique to this time period or to Judaism. For example, Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite and Maximus the Confessor, Eastern Christian theologians, developed apophatic theology for Christianity nearly 900 years earlier. See Negative theology for uses in other religions.

Prophecy

He agrees with "the philosophers" in teaching that, man's intelligence being one in the series of intelligences emanating from God, the prophet must, by study and meditation, lift himself up to the degree of perfection required in the prophetic state. But here, he invokes the authority of "the Law," which teaches that, after that perfection is reached, there is required the "free acts of God," before the man actually becomes a prophet.

The problem of evil

Maimonides wrote on theodicy (the philosophical attempt to reconcile the existence of a God with the existence of evil in the world). He took the premise that an omnipotent and good God exists. He adopts the Aristotelian view that defines evil as the lack of, or the reduced presence of a God, as exhibited by those who exercise the free choice of rejecting belief.

True beliefs versus necessary beliefs

In "Guide for the Perplexed" Book III, Chapter 28[15], Maimonides explicitly draws a distinction between "true beliefs," which were beliefs about God which produced intellectual perfection, and "necessary beliefs," which were conducive to improving social order. Maimonides places anthropomorphic personification statements about God in the latter class. He uses as an example the notion that God becomes "angry" with people who do wrong. In the view of Maimonides (taken from Avicenna) God does not actually become angry with people, as God has no human passions; but it is important for them to believe God does, so that they desist from sinning.

Resurrection, acquired immortality, and the afterlife

Resurrection, acquired immortality, and the afterlife

Maimonides distinguishes two kinds of intelligence in man, the one material in the sense of being dependent on, and influenced by, the body, and the other immaterial, that is, independent of the bodily organism. The latter is a direct emanation from the universal active intellect; this is his interpretation of the noûs poietikós of Aristotelian philosophy. It is acquired as the result of the efforts of the soul to attain a correct knowledge of the absolute, pure intelligence of God.

The knowledge of God is a form of knowledge which develops in us the immaterial intelligence, and thus confers on man an immaterial, spiritual nature. This confers on the soul that perfection in which human happiness consists, and endows the soul with immortality. One who has attained a correct knowledge of God has reached a condition of existence which renders him immune from all the accidents of fortune, from all the allurements of sin, and even from death itself. Man, therefore is in a position not only to work out his own salvation and immortality.

The resemblance between this doctrine and Spinoza's doctrine of immortality is so striking as to warrant the hypothesis that there is a causal dependence of the latter on the earlier doctrine. The differences between the two Jewish thinkers are, however, as remarkable as the resemblance. While Spinoza teaches that the way to attain the knowledge which confers immortality is the progress from sense-knowledge through scientific knowledge to philosophical intuition of all things sub specie æternitatis, Maimonides holds that the road to perfection and immortality is the path of duty as described in the Torah and the rabbinic understanding of the oral law.

Religious Jews not only believed in immortality in some spiritual sense, but most believed that there would at some point in the future be a messianic era, and a resurrection of the dead. This is the subject of Jewish eschatology. Maimonides wrote much on this topic, but in most cases he wrote about the immortality of the soul for people of perfected intellect; his writings were usually not about the resurrection of dead bodies. This prompted hostile criticism from the rabbis of his day, and sparked a controversy over his true views.

Rabbinic works usually refer to this afterlife as "Olam Haba" (the World to Come). Some rabbinic works use this phrase to refer to a messianic era, an era of history right here on Earth; in other rabbinic works this phrase refers to a purely spiritual realm. It was during Maimonides's lifetime that this lack of agreement flared into a full blown controversy, with Maimonides charged as a heretic by some Jewish leaders.

Some Jews at this time taught that Judaism did not require a belief in the physical resurrection of the dead, as the afterlife would be a purely spiritual realm. They used Maimonides's works on this subject to back up their position. In return, their opponents claimed that this was outright heresy; for them the afterlife was right here on Earth, where God would raise dead bodies from the grave so that the resurrected could live eternally. Maimonides was brought into this dispute by both sides, as the first group stated that his writings agreed with them, and the second group portrayed him as a heretic for writing that the afterlife is for the immaterial spirit alone. Eventually, Maimonides felt pressured to write a treatise on the subject, the "Ma'amar Tehiyyat Hametim" "The Treatise on Resurrection."

Chapter two of the treatise on resurrection refers to those who believe that the world to come involves physically resurrected bodies. Maimonides refers to one with such beliefs as being an "utter fool" whose belief is "folly".

- If one of the multitude refuses to believe [that angels are incorporeal] and prefers to believe that angels have bodies and even that they eat, since it is written (Genesis 18:8) 'they ate', or that those who exist in the World to Come will also have bodies—we won't hold it against him or consider him a heretic, and we will not distance ourselves from him. May there not be many who profess this folly, and let us hope that he will go no farther than this in his folly and believe that the Creator is corporeal.

However, Maimonides also writes that those who claimed that he altogether believed the verses of the Hebrew Bible referring to the resurrection were only allegorical were spreading falsehoods and "revolting" statements. Maimonides asserts that belief in resurrection is a fundamental truth of Judaism about which there is no disagreement, and that it is not permissible for a Jew to support anyone who believes differently. He cites Daniel 12:2 and 12:13 as definitive proofs of physical resurrection of the dead when they state "many of them that sleep in the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life and some to reproaches and everlasting abhorrence" and "But you, go your way till the end; for you shall rest, and will arise to your inheritance at the end of the days."

While these two positions may be seen as in contradiction (non-corporeal eternal life, versus a bodily resurrection), Maimonides resolves them with a then unique solution: Maimonides believed that the resurrection was not permanent or general. In his view, God never violates the laws of nature. Rather, divine interaction is by way of angels, which Maimonides often regards to be metaphors for the laws of nature, the principles by which the physical universe operates, or Platonic eternal forms. [This is not always the case. In Hilchot Yesodei HaTorah Chaps. 2-4, Maimonides describes angels that are actually created beings.] Thus, if a unique event actually occurs, even if it is perceived as a miracle, it is not a violation of the world's order.

In this view, any dead who are resurrected must eventually die again. In his discussion of the 13 principles of faith, the first five deal with knowledge of God, the next four deal with prophecy and the Torah, while the last four deal with reward, punishment and the ultimate redemption. In this discussion Maimonides says nothing of a universal resurrection. All he says it is that whatever resurrection does take place, it will occur at an indeterminate time before the world to come, which he repeatedly states will be purely spiritual.

He writes "It appears to us on the basis of these verses (Daniel 12:2,13) that those people who will return to those bodies will eat, drink, copulate, beget, and die after a very long life, like the lives of those who will live in the Days of the Messiah." Maimonides thus disassociated the resurrection of the dead from both the World to Come and the Messianic era.

In his time, many Jews believed that the physical resurrection was identical to the world to come; thus denial of a permanent and universal resurrection was considered tantamount to denying the words of the Talmudic sages. However, instead of denying the resurrection, or maintaining the current dogma, Maimonides posited a third way: That resurrection had nothing to do with the messianic era (here in this world) nor to do with Olam Haba (עולם הבא) (the purely spiritual afterlife). Rather, he considered resurrection to be a miracle that the book of Daniel predicted; thus at some point in time we could expect some instances of resurrection to occur temporarily, which would have no place in the final eternal life of the righteous.

Maimonides remains the most widely debated Jewish thinker among modern scholars. He has been adopted as a symbol and an intellectual hero by almost all major movements in modern Judaism, and has proven immensely important to philosophers such as Leo Strauss; and his views on the importance of humility have been taken up by modern humanist philosophers, like Peter Singer and Iain King. In academia, particularly within the area of Jewish Studies, the teaching of Maimonides has been dominated by traditional, generally Orthodox scholars, who place a very strong emphasis on Maimonides as a rationalist. The result of this is many sides of Maimonides's thought, for example his opposition to anthropocentrism, have been obviated. There is some movement in postmodern circles, e.g. within the discourse of ecotheology, to claim Maimonides for other purposes. Maimonides's reconciliation of the philosophical and the traditional has given his legacy an extremely diverse and dynamic quality.

Maimonides has been memorialized in numerous ways. For example, one of the Learning Communities at the Tufts University School of Medicine bears his name. There is also Maimonides School in Brookline, Massachusetts, the Brauser Maimonides Academy in Hollywood, Florida, and Maimonides Medical Center in Brooklyn, New York. In 2004, conferences were held at Yale, Florida International University, Penn State, and the Rambam hospital in Haifa. To commemorate the 800th anniversary of his death, Harvard University issued a memorial volume. In 1953, the Israel Postal Authority issued a postage stamp of Maimonides, pictured. In March 2008, during the Euromed Conference of Ministers of Tourism, The Tourism Ministries of Israel, Morocco and Spain agreed to work together on a joint project that will trace the footsteps of the Rambam and thus boost religious tourism in the cities of Córdoba, Fez and Tiberias.

Moses Maimonidész (vagy Majmonidész, 1137 / 1138 – 1204), teljes nevén Mose ben Maimon (héberül: משה בן מימון), saját nyelvén, arabul: موسى بن ميمون بن عبد الله القرطبي الإسرائيلي (Múszá ibn Majmún ibn Abdalláh al-Kurtubí al-Iszráílí), zsidó rabbi, orvos, filozófus; Spanyolországban és Egyiptomban tevékenykedett a középkorban. Héber nyelvű művekben Maimoni (מימוני) néven említik, de találkozunk a Mose ben Maimon rabbi névváltozattal és ennek héber rövidítésével RáMBáM formával is.

Moses Maimonidész (vagy Majmonidész, 1137 / 1138 – 1204), teljes nevén Mose ben Maimon (héberül: משה בן מימון), saját nyelvén, arabul: موسى بن ميمون بن عبد الله القرطبي الإسرائيلي (Múszá ibn Majmún ibn Abdalláh al-Kurtubí al-Iszráílí), zsidó rabbi, orvos, filozófus; Spanyolországban és Egyiptomban tevékenykedett a középkorban. Héber nyelvű művekben Maimoni (מימוני) néven említik, de találkozunk a Mose ben Maimon rabbi névváltozattal és ennek héber rövidítésével RáMBáM formával is.

Az ő nevéhez fűződik a zsidó vallásjog (halakha) törvényeinek a rendszerbe foglalása (Misné Tórá) a Talmud alapján.

1137/38-ban született Córdobában, ami az ő korában az arab kultúra egyik központja volt. (A korábbi szakirodalomban szereplő 1135-ös születési dátum téves.) Tanulmányait kezdetben apja útmutatása mellett végezte, aki rabbinikus bíró (dajján) volt. De ugyanekkor ismerkedett meg az antik görög és arab filozófiával is, arab tudósok közvetítésével.

Mikor 1148-ban, Spanyolországban a fanatikus muszlim Almohád-mozgalom hatására a zsidó lakosságot kényszerítették vallásuk elhagyására, Maimonidész családja inkább a száműzetést választotta és Észak-Afrikába menekült. 1159-ben a család a marokkói, Fez nevű városban telepedett le, majd 1165-be Jeruzsálembe költözött. Innen Egyiptomba költöztek tovább, először Alexandria városba, majd a mai Kairó helyén állt Fusztát nevű városba, ahol Maimonidész életének végéig élt.

A család vándorlása közben Maimonidész nem hagyta abba a tanulmányait: orvoslást tanult és Arisztotelészt és egyéb filozófiai műveket tanulmányozott. Fusztátban Maimonidész a rabbinikus bíróság tagja, és egy nem bizonyított hipotézis szerint a zsidó közösség vezetője (Nagid, vagy raisz al-jahud) lett, majd 1185-től Szaladin, Egyiptom és Szíria ajjúbida szultánjának a személyes orvosa. Mindez idő közben számos művet és tanulmányt írt. Írt egy filozófiai logikával foglalkozó művet (aminek autenticitását újabban kétségbevonják); egy judeo-arab nyelvű kommentárt a Misnához; a Tóra 613 parancsának felsorolását (Széfer ha-micvot); a Misné Torá törvénykönyvet; A tévelygők útmutatója című judeo-arabul írt filozófiai értekezlést, továbbá számos levelét, amelyeket különböző zsidó közösségeknek írt. Misna-kommentár eredetileg arab nyelven íródott, majd később fordították héber nyelvre.

Maimonidésznek különösen a Misné Torá című munkája ismert. Ebben összefoglalja a zsidó vallásjog (halakha) teljes anyagát. Eltérve a korábbi hagyománytól Maimonidész nem tárgyalja a törvények talmudi forrásait. Ehelyett arra törekszik, hogy a zsidó vallást logikus egészként mutassa be. Második legfontosabb műve a Tévelygők útmutatója. Ebben a műben azokhoz fordult, akik a filozófiával való foglalkozás közben hitükben elbizonytalanodtak, és azt akarja megmutatni, hogy hogyan válhat a hit sajáttá a tudomány közvetítésével: ahol a tudományos ismeretek ellentmondanak a bibliai szövegnek, ott allegorikusan kell értelmezni azokat.

Maimonidész negatív teológiát képvisel, ami azt jelenti, hogy Isten lényegéről csak tagadó módon lehet beszélni. Az állítások csak Isten hatásaira vonatkoznak és nem a lényegére.

A 13 hittétel

Maimonidész a zsidó vallás tanait, a Misna kommentárokban (Sanhedrin, 10. fejezet) 13 hittételben foglalta össze:

- A Teremtő Istenben hiszek.

- Isten egyetlen

- Isten szellemi lény.

- Isten az első és utolsó.

- Istenen kívül senki sem méltó az imádásra.

- A próféták szavai igazak.

- Mózes a próféták atyja.

- A mai Tóra a Mózesnek átadottal megegyezik.

- Nincs más Tóra.

- Isten ismeri az ember gondolatát, tud tetteikről, megérti minden tettünket.

- Isten a parancs meg nem tartóját bünteti, a megőrzőit jóval fizeti.

- Hit az eljövendő Messiásban, és az ő várása.

- Hit a holtak feltámadásban.

.jpg)